The Western Diet not only Damages the Body—It Damages the Mind

It has long been understood that one’s diet has a significant effect on their physiological health, affecting factors such as body mass index, general energy levels, and organ function. The Western diet, in particular, is characterized by the frequent consumption of sugar and foods which are high in saturated fat but deficient in fruits and vegetables as well as vitamins, minerals, and flavonoids. This diet is known to increase risks for heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and even cancer. Less obvious with any diet, however, is the effect of one’s eating habits on emotional health and cognitive ability.

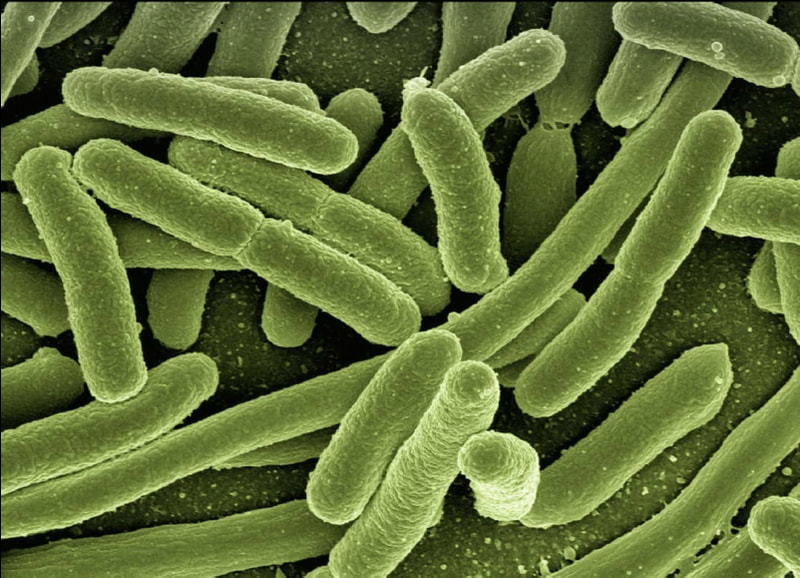

The connection between our food consumption and psychological health is mediated by the hippocampus, a brain structure which controls memory, learning, emotional regulation, and cognition. Likewise, atrophy of the hippocampus has been linked to cognitive decline and emotional irregularity. With the loss of these functions, memory disorders such as dementia, and mood disorders such as Major Depressive Disorder, have a greater risk of quicker development. As such, new studies have focused on identifying the cause of both hippocampal neurogenesis and atrophy to better understand health and nutrition.

The connection between our food consumption and psychological health is mediated by the hippocampus, a brain structure which controls memory, learning, emotional regulation, and cognition. Likewise, atrophy of the hippocampus has been linked to cognitive decline and emotional irregularity. With the loss of these functions, memory disorders such as dementia, and mood disorders such as Major Depressive Disorder, have a greater risk of quicker development. As such, new studies have focused on identifying the cause of both hippocampal neurogenesis and atrophy to better understand health and nutrition.

Image Source: dbreen

In a non-blinded study exploring the relationship between diet and psychological health, researchers examined a link between the Western diet and emotional and cognitive decline. They drew two subsets of data, examining brain scans, diet, and health profiles, from a larger study called the Personality and Total Health (PATH) Through Life project. This study examined 255 randomly-selected individuals between ages 60-64 from a much larger group of people who all received magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of their hippocampus before and after a four-year period.

Participants were divided into three groups based on their existing eating habits: Western (“bad”) diet, “average” diet, and “good” diet. For both ethical and practical reasons, subjects self-reported what they ate, meaning that researchers had to trust the information communicated by the participants, creating an information bias. However, because factors such as education, activity level, and body mass index were essentially the same across these groups, any differences in health and cognition in subjects was generally attributed to differences in diet alone.

The results of the study showed that the volume of the left hippocampus significantly increased as diets improved, over the four-year duration. However, there was no trend between diet quality and hippocampal atrophy for the right half. In other words, the consumption of a Western diet most likely accelerates hippocampal volume atrophy for the left half of the hippocampus (as this group experienced the most left hippocampal atrophy), but not the right half.

The link between diet and hippocampal volume demonstrated by this research emphasizes the direct influence of one’s eating habits on brain structure and, thus, mental and emotional fitness. By incorporating a wide variety of nutrients such as fruits, vegetables, and vitamins into one’s diet while limiting sugar and saturated fat, one can essentially slow the aging process of the brain beyond maintaining the body’s physical health.

Participants were divided into three groups based on their existing eating habits: Western (“bad”) diet, “average” diet, and “good” diet. For both ethical and practical reasons, subjects self-reported what they ate, meaning that researchers had to trust the information communicated by the participants, creating an information bias. However, because factors such as education, activity level, and body mass index were essentially the same across these groups, any differences in health and cognition in subjects was generally attributed to differences in diet alone.

The results of the study showed that the volume of the left hippocampus significantly increased as diets improved, over the four-year duration. However, there was no trend between diet quality and hippocampal atrophy for the right half. In other words, the consumption of a Western diet most likely accelerates hippocampal volume atrophy for the left half of the hippocampus (as this group experienced the most left hippocampal atrophy), but not the right half.

The link between diet and hippocampal volume demonstrated by this research emphasizes the direct influence of one’s eating habits on brain structure and, thus, mental and emotional fitness. By incorporating a wide variety of nutrients such as fruits, vegetables, and vitamins into one’s diet while limiting sugar and saturated fat, one can essentially slow the aging process of the brain beyond maintaining the body’s physical health.

Featured Image Source: pencilparker

RELATED ARTICLES

|

Vertical Divider

|

Vertical Divider

|

Vertical Divider

|