Success Sparks More Gene Therapy Trials

According to the American Institute for Cancer Research, cancer ranks the highest among Americans’ health concerns. Cancer is greatly feared among the public due to its prevalence, the long and painful treatments, and the current lack of technology for a cure. Researches have been developing new methods to treat cancer. One method, gene therapy, has been newly approved for administration on HIV and leukemia patients as a trial run.

Gene therapy is a method that modifies DNA by adding, removing, or altering the DNA genome. Changes to the DNA genome can affect certain characteristics of a cell or organism. For example, this method can help produce higher yields of crops by editing the crops’ DNA to have a higher tolerance to disease and drought. In the medical world, gene therapy is used to treat diseases and infections by modifying the DNA that causes abnormalities. In the case of HIV and leukemia, enzymes are used to modify specific DNA sequences to protect the patient’s immune cells.

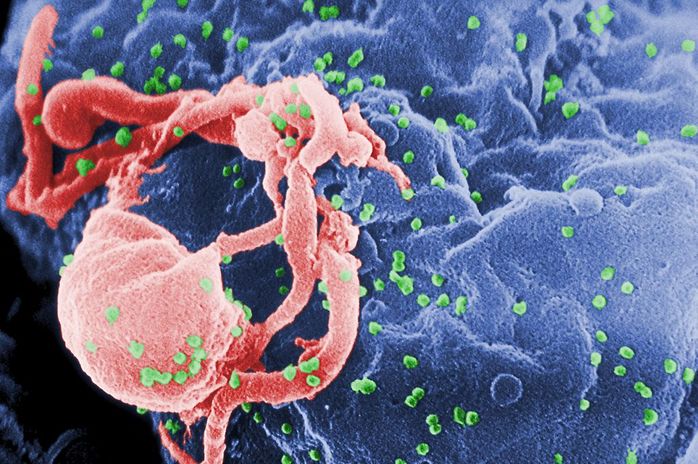

HIV and leukemia cause death by weakening the patient’s immune system and making those affected extremely susceptible to infections. Sangamo BioSciences from Richmond, California first used gene therapy trials to treat HIV patients. In this treatment, they used an enzyme called zinc-finger nuclease (ZFN) to cut out the DNA that codes for a specific T-cell protein targeted by HIV. First, blood was extracted from HIV patients, and ZFN was added to the extracted blood. ZFN, then, prevented HIV from targeting a specific protein so that it could not affect new cells. Once the ZFN finished its job, the blood is pumped back into a patient’s body, boosting his or her immune system. This treatment proved effective, as half of the patients treated no longer had to take their antiretroviral drugs. The success in this treatment led to a second trial of gene therapy usage.

Immunologist Waseem Qasim of Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust and his team in London carried out a different form of gene therapy on Layla, a one-year-old leukemia patient. In this form of treatment, the patient’s immune system is destroyed and replaced with healthy modified immune cells from a donor. T-cells extracted from the donor are treated with the enzyme TALEN, which modifies the cells so they do not attack the leukemia patient when injected. The donor cells must also be further modified so that anti-cancer drugs taken by the patient do not affect them. When this treatment was applied to Layla, it was successful, and she is currently in remission. Although this treatment for leukemia patients is not a permanent solution, it can sustain the patient’s life long enough to find a matched T-cell donor.

Gene therapy is a method that modifies DNA by adding, removing, or altering the DNA genome. Changes to the DNA genome can affect certain characteristics of a cell or organism. For example, this method can help produce higher yields of crops by editing the crops’ DNA to have a higher tolerance to disease and drought. In the medical world, gene therapy is used to treat diseases and infections by modifying the DNA that causes abnormalities. In the case of HIV and leukemia, enzymes are used to modify specific DNA sequences to protect the patient’s immune cells.

HIV and leukemia cause death by weakening the patient’s immune system and making those affected extremely susceptible to infections. Sangamo BioSciences from Richmond, California first used gene therapy trials to treat HIV patients. In this treatment, they used an enzyme called zinc-finger nuclease (ZFN) to cut out the DNA that codes for a specific T-cell protein targeted by HIV. First, blood was extracted from HIV patients, and ZFN was added to the extracted blood. ZFN, then, prevented HIV from targeting a specific protein so that it could not affect new cells. Once the ZFN finished its job, the blood is pumped back into a patient’s body, boosting his or her immune system. This treatment proved effective, as half of the patients treated no longer had to take their antiretroviral drugs. The success in this treatment led to a second trial of gene therapy usage.

Immunologist Waseem Qasim of Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust and his team in London carried out a different form of gene therapy on Layla, a one-year-old leukemia patient. In this form of treatment, the patient’s immune system is destroyed and replaced with healthy modified immune cells from a donor. T-cells extracted from the donor are treated with the enzyme TALEN, which modifies the cells so they do not attack the leukemia patient when injected. The donor cells must also be further modified so that anti-cancer drugs taken by the patient do not affect them. When this treatment was applied to Layla, it was successful, and she is currently in remission. Although this treatment for leukemia patients is not a permanent solution, it can sustain the patient’s life long enough to find a matched T-cell donor.

Image Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

However, this treatment may have drawbacks. These approaches work for blood-related diseases, but alternatives must be found when the organs are affected. Furthermore, these procedures must be done within the body. Both methods of gene therapy raise some concerns about mutations within the genome, but direct gene therapy on organs and tissues is very risky compared to the methods described above. One concern would be that the DNA-delivering vector would continue to treat the patient more than necessary. Another concern is that the patient may have an immune response to the DNA-cutting enzyme. More difficulties include ensuring that the DNA-delivering vector edits the genome at the right part of the body and that it edits enough target cells to produce a positive effect. Using a vector is currently being tested on animals but has not been tried on humans. Although there have not been any ill effects found in the treated animals, these concerns must be addressed before the method can be implemented.

The successes of the treatment on HIV patients and Layla, however, have cleared the road for testing on further cancer patients. A US National Institutes of Health committee in charge of approving clinical trials allowed Sangamo to test gene therapy on patients with factor-IX. Once Sangamo receives approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), it can begin its trials. Other companies have also taken interest in testing gene therapy on humans. Editas Medicine in Cambridge, Massachusetts hopes to cure Leber congenital amaurosis by using gene therapy to fix a mutation-induced retinal disorder. After much more testing, gene therapy may eventually be administered, bringing hope to all afflicted with these serious complications.

The successes of the treatment on HIV patients and Layla, however, have cleared the road for testing on further cancer patients. A US National Institutes of Health committee in charge of approving clinical trials allowed Sangamo to test gene therapy on patients with factor-IX. Once Sangamo receives approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), it can begin its trials. Other companies have also taken interest in testing gene therapy on humans. Editas Medicine in Cambridge, Massachusetts hopes to cure Leber congenital amaurosis by using gene therapy to fix a mutation-induced retinal disorder. After much more testing, gene therapy may eventually be administered, bringing hope to all afflicted with these serious complications.

Featured Image Source: "cure cancer. please?" by Billie.Stock.Photography is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

RELATED ARTICLES

|

Vertical Divider

|

Vertical Divider

|

Vertical Divider

|