How Extreme Heat will Impact Californians

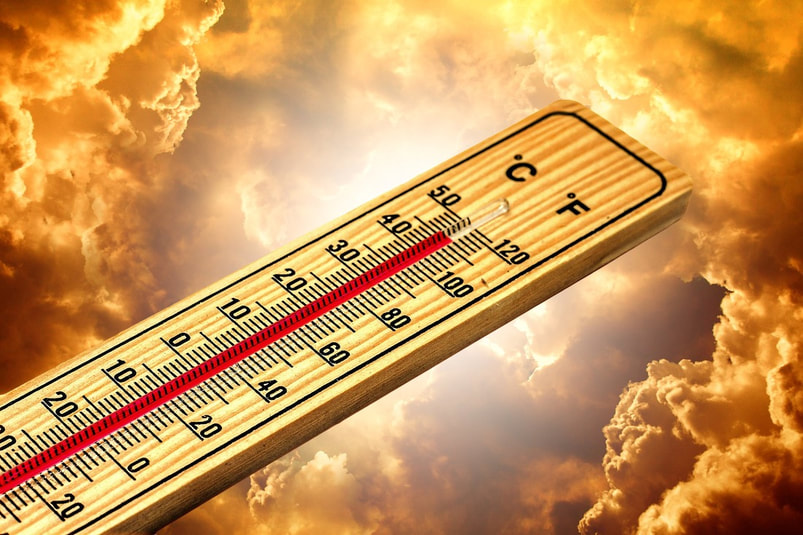

Extreme weather events, from record-breaking hurricanes and wildfires to severe droughts, have already increased in frequency as a result of climate change. Many Californians are especially cognizant of the hazards posed by a longer and more destructive fire season and rising sea-levels on the coast. A looming threat that must be mitigated to prevent the loss of life is the increasing number of extreme heat events across the state. From 1999 to 2009, 15 heat waves in California led to 11,000 hospitalizations. Like many other environmental exposures, the threat that extreme heat poses on communities is not equitable. It is heavily impacted by economic and regional factors, as well as historical discriminatory zoning practices which targeted many nonwhite communities.

The state of California utilizes an index, CalEnviroScreen (CES), in order to identify communities to receive funding that can go towards the necessary infrastructure, adaptations, and modifications needed to address the significant impacts of climate change and pollution. The state currently utilizes the CES to assess heat risk, but because its primary focus is air and water pollution, its ability to accurately assess heat vulnerability is questionable.

The state of California utilizes an index, CalEnviroScreen (CES), in order to identify communities to receive funding that can go towards the necessary infrastructure, adaptations, and modifications needed to address the significant impacts of climate change and pollution. The state currently utilizes the CES to assess heat risk, but because its primary focus is air and water pollution, its ability to accurately assess heat vulnerability is questionable.

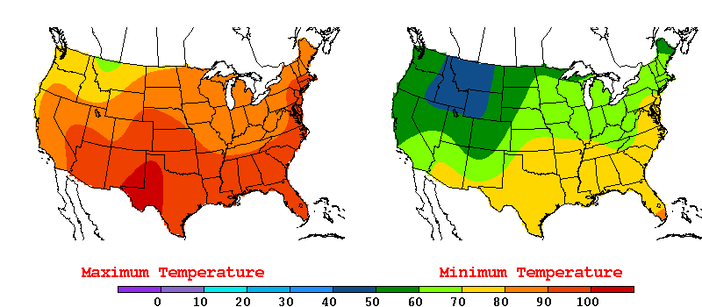

Image Source: "2016-07-07 Color Max-min Temperature Map NOAA" by National Centers for Environmental Prediction is licensed under Public Domain

Stanford researchers compared the currently-used index with two other indices in census-tracts across California in order to compare how each index quantified heat risk in different regions. The researchers then compared this data with the distribution of existing projects funded through the California Climate Investments program (CCI) across communities at risk from extreme heat.

The two other indices used were the Heat-Health Action Index (HHAI) and the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI). The HHAI measures communities’ susceptibility to extreme heat events, while the SVI is a more general index used to assess disaster readiness. Each index received an assessment based on its choice of demographic, economic, health, and environmental factors. When examining heat events, the researchers measured extreme heat events in both relative and absolute terms. The relative extreme heat threshold was a temperature that was in the 95th percentile, meaning hotter than 95% of all previously recorded temperatures for that day. The absolute extreme heat threshold was a temperature of at least 91°F.

The researchers found that an additional 12.7% of California census-tracts, which are not currently included under the current CalEnviroScreen index, should be considered at high heat risk. Census-tracts that were vulnerable under the pollution-based index, but not the heat-based index, were more likely to receive funding for heat-interventions than census-tracts that were vulnerable under just the heat-based index. In fact, those vulnerable under the pollution-based index received four times the number of interventions. This discrepancy emphasizes that there are many communities in need of the infrastructure to deal with future heat crises that are currently being left out of the investment program due to gaps in the current CES index.

In addition to the need for more accurate quantitative measurements, the researchers note that for a state as large and diverse as California, they must assess this data in conjunction with direct observation within communities. No matter how sophisticated the index, communities must be directly consulted to account for the realities that can not be fully conveyed through data.

Infrastructure that can provide a safe, cool environment can save the lives of those most at risk for heat injury— people who are unhoused, elderly, disabled, chronically ill, or very young. It is a necessary effort, but only one of many. The effects of climate change are varied and far reaching, from the destabilization of ecosystems to increasing the likelihood of infectious diseases spreading from animals to humans. Every effort to mitigate the impacts of climate change must also be supported by aggressive action to combat climate change itself.

The two other indices used were the Heat-Health Action Index (HHAI) and the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI). The HHAI measures communities’ susceptibility to extreme heat events, while the SVI is a more general index used to assess disaster readiness. Each index received an assessment based on its choice of demographic, economic, health, and environmental factors. When examining heat events, the researchers measured extreme heat events in both relative and absolute terms. The relative extreme heat threshold was a temperature that was in the 95th percentile, meaning hotter than 95% of all previously recorded temperatures for that day. The absolute extreme heat threshold was a temperature of at least 91°F.

The researchers found that an additional 12.7% of California census-tracts, which are not currently included under the current CalEnviroScreen index, should be considered at high heat risk. Census-tracts that were vulnerable under the pollution-based index, but not the heat-based index, were more likely to receive funding for heat-interventions than census-tracts that were vulnerable under just the heat-based index. In fact, those vulnerable under the pollution-based index received four times the number of interventions. This discrepancy emphasizes that there are many communities in need of the infrastructure to deal with future heat crises that are currently being left out of the investment program due to gaps in the current CES index.

In addition to the need for more accurate quantitative measurements, the researchers note that for a state as large and diverse as California, they must assess this data in conjunction with direct observation within communities. No matter how sophisticated the index, communities must be directly consulted to account for the realities that can not be fully conveyed through data.

Infrastructure that can provide a safe, cool environment can save the lives of those most at risk for heat injury— people who are unhoused, elderly, disabled, chronically ill, or very young. It is a necessary effort, but only one of many. The effects of climate change are varied and far reaching, from the destabilization of ecosystems to increasing the likelihood of infectious diseases spreading from animals to humans. Every effort to mitigate the impacts of climate change must also be supported by aggressive action to combat climate change itself.

Featured Image Source: geralt

RELATED ARTICLES

|

Vertical Divider

|

Vertical Divider

|

Vertical Divider

|