How Chronic Stress Damages the Brain

Stress is the entirety of the physiological and behavioral changes the body experiences due to external factors which put pressure on it. When the body perceives an event as threatening or challenging to its well-being, it triggers a series of biological mechanisms which provoke the body into an aroused state. Being wired as a temporary survival mechanism, long-term activation of this strong response damages the body and especially the brain, leading to cognitive impairments and mental health disorders.

The stress response is rooted in the brain’s limbic system, which dictates emotion and motivation. When the brain detects a stressful situation, one such limbic structure, the hypothalamus, directs a chemical signal which reaches the adrenal glands leading to a surge of arousing hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol. The release of these fight-or-flight chemicals into the bloodstream increases blood sugar levels and quickens heart rate, breathing, and reaction time. The body’s metabolism also elevates—cells harvest energy from glucose— leading to a quick boost of energy, focus, and muscle strength.

Because of this, however, the stress response consumes an exorbitant amount of energy in order to give an individual that sudden energy boost. It consumes a fraction of the body’s limited total energy supply so it can be used by the muscles before it’s lost as heat. This energetically-taxing process becomes a problem when it is enduring because eventually so much of the body’s energy supply is lost that its cells can no longer function properly, affecting the overall health of the individual.

Chronic stress is particularly problematic for the brain, an organ which is especially energy-consuming. Because of its billions of cells and intricate neural connections, the brain requires at least 30% of the body’s total energy supply just to maintain its function. Also, because of its significant energy demand, any changes to its cells’ metabolic rate will have drastic effects on an individual’s health. Likewise, when the body activates the stress response, energy is withdrawn from the brain— the center for rational thought and decision-making— in order to prioritize compulsory muscular action.

In a study which used animals to track the long-term consequences of sustained stress, researchers found that these conditions led to significant cognitive impairments as a result of drastic changes to the brain’s ability to metabolize glucose. After experiencing stress-inducing environments for prolonged time periods, nearly all subjects suffered from damaged cognitive functioning and decimated memory retrieval; this was attributed to brain cells’ decreased ability to uptake glucose. As a consequence, these animals’ brains not only failed to use sufficient energy to perform their basic functions in the nervous system, but the accumulation of sugar in the surrounding blood vessels and tissues led to hyperglycemia.

The stress response is rooted in the brain’s limbic system, which dictates emotion and motivation. When the brain detects a stressful situation, one such limbic structure, the hypothalamus, directs a chemical signal which reaches the adrenal glands leading to a surge of arousing hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol. The release of these fight-or-flight chemicals into the bloodstream increases blood sugar levels and quickens heart rate, breathing, and reaction time. The body’s metabolism also elevates—cells harvest energy from glucose— leading to a quick boost of energy, focus, and muscle strength.

Because of this, however, the stress response consumes an exorbitant amount of energy in order to give an individual that sudden energy boost. It consumes a fraction of the body’s limited total energy supply so it can be used by the muscles before it’s lost as heat. This energetically-taxing process becomes a problem when it is enduring because eventually so much of the body’s energy supply is lost that its cells can no longer function properly, affecting the overall health of the individual.

Chronic stress is particularly problematic for the brain, an organ which is especially energy-consuming. Because of its billions of cells and intricate neural connections, the brain requires at least 30% of the body’s total energy supply just to maintain its function. Also, because of its significant energy demand, any changes to its cells’ metabolic rate will have drastic effects on an individual’s health. Likewise, when the body activates the stress response, energy is withdrawn from the brain— the center for rational thought and decision-making— in order to prioritize compulsory muscular action.

In a study which used animals to track the long-term consequences of sustained stress, researchers found that these conditions led to significant cognitive impairments as a result of drastic changes to the brain’s ability to metabolize glucose. After experiencing stress-inducing environments for prolonged time periods, nearly all subjects suffered from damaged cognitive functioning and decimated memory retrieval; this was attributed to brain cells’ decreased ability to uptake glucose. As a consequence, these animals’ brains not only failed to use sufficient energy to perform their basic functions in the nervous system, but the accumulation of sugar in the surrounding blood vessels and tissues led to hyperglycemia.

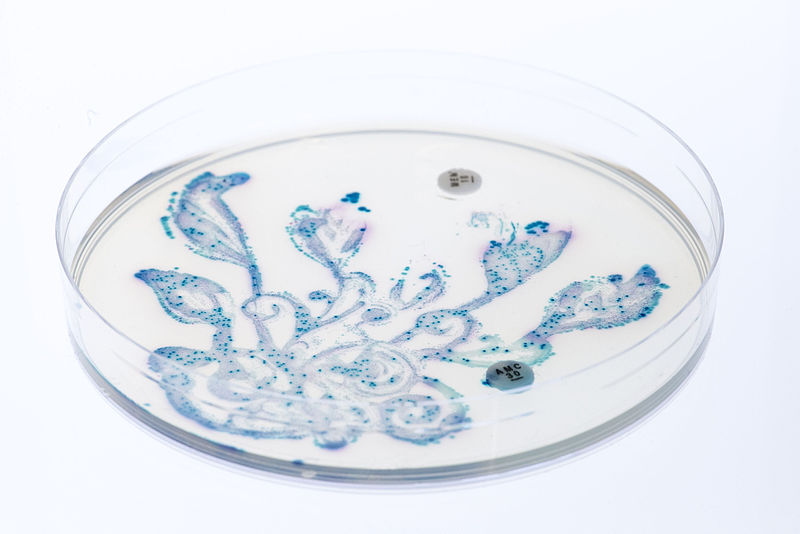

Image Source: grafikacesky

Cognitive disorders begin to arise when these effects of high glucose and cortisol concentrations inflict structural damage of the brain’s structures, particularly the hippocampus. Beyond playing a role in dictating the stress response itself, the hippocampus also regulates the formation and retrieval of memory. With the loss of these functions, memory disorders such as dementia and Alzheimer’s develop more rapidly. Mood disorders, such as Major Depressive Disorder, also correlate with decreased hippocampal volume; individuals who have anxiety increase their risk of developing depression later in life if stress is chronic.

Nonetheless, stress and its long term effects are still manageable. In fact, steps individuals can take to lower their stress involve simple lifestyle changes such as getting more sleep, exercising, and meditation.

Nonetheless, stress and its long term effects are still manageable. In fact, steps individuals can take to lower their stress involve simple lifestyle changes such as getting more sleep, exercising, and meditation.

Featured Image Source: TheDigitalArtist

RELATED ARTICLES

|

Vertical Divider

|

Vertical Divider

|

Vertical Divider

|