Approaching Immunotherapy with Helper T Cells

In their search for a cure to cancer, scientists have turned to the immune system as an invaluable tool. Cancer cells are different from normal, healthy cells since they have mutations that allow them to multiply uncontrollably. This difference could theoretically allow for immune cells to identify and kill them, as the role of the immune system is to rid the body of abnormal or foreign pathogens and mutated cells. Development of this idea led to the expansion of immunotherapy, a form of cancer therapy that uses the immune system to fight cancer, throughout the 20th century. New research from the Washington University School of Medicine in Saint Louis continues to improve upon immunotherapy approaches, specifically in how Helper T cells can be used.

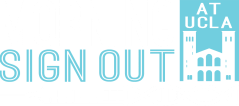

When the body identifies a cancerous cell, Cytotoxic T cells will begin to target and destroy them if they can bind with a specific substance present on the surface of the cancer cell. This substance is called an antigen. There are multiple variations of T cells, each one pairing to a different antigen. When a T cell interacts with a new antigen, it replicates itself to increase the chance of that antigen being destroyed if it appears in the future. One form of immunotherapy involves giving a cancer patient more antigens for their specific cancer. This tricks the immune system into thinking that there are more of these cancer cells than there actually are, and subsequently kicks the immune system into a higher level of activity.

When the body identifies a cancerous cell, Cytotoxic T cells will begin to target and destroy them if they can bind with a specific substance present on the surface of the cancer cell. This substance is called an antigen. There are multiple variations of T cells, each one pairing to a different antigen. When a T cell interacts with a new antigen, it replicates itself to increase the chance of that antigen being destroyed if it appears in the future. One form of immunotherapy involves giving a cancer patient more antigens for their specific cancer. This tricks the immune system into thinking that there are more of these cancer cells than there actually are, and subsequently kicks the immune system into a higher level of activity.

However, this method is not always effective, leading to the researcher’s efforts surrounding Helper T cells as ways to increase treatment efficiency. Like normal Cytotoxic T cells, Helper T cells also recognize antigens, but do so on the surfaces of antigen-packed dendritic cells. After a Helper T cell recognizes the antigen, it sends out cytokines, chemicals that signal the Cytotoxic T cells to multiply and work harder.

The researchers also noted that in many cases, not all existing Cytotoxic T cells are activated and some may need additional Helper T cells to start working. When the researchers studied mice with cancer who were treated with both Helper T cells and Cytotoxic T cells, they found that treatments with Helper T cells were more effective than those with only Cytotoxic T cells. Utilizing Helper T cells then could make immunotherapy treatments more effective, since they can amplify the Cytotoxic T cell response in cancer patients.

This new research hopes to increase the chance that an immunotherapy treatment will be effective on a cancer patient. This further paves the way for scientists to learn how to tweak other components of the immune system to better support the Cytotoxic T cell’s protective role, and further demonstrates the treasure trove of immune information yet to be unlocked.

The researchers also noted that in many cases, not all existing Cytotoxic T cells are activated and some may need additional Helper T cells to start working. When the researchers studied mice with cancer who were treated with both Helper T cells and Cytotoxic T cells, they found that treatments with Helper T cells were more effective than those with only Cytotoxic T cells. Utilizing Helper T cells then could make immunotherapy treatments more effective, since they can amplify the Cytotoxic T cell response in cancer patients.

This new research hopes to increase the chance that an immunotherapy treatment will be effective on a cancer patient. This further paves the way for scientists to learn how to tweak other components of the immune system to better support the Cytotoxic T cell’s protective role, and further demonstrates the treasure trove of immune information yet to be unlocked.

Featured Image Source: stevepb

RELATED ARTICLES

|

Vertical Divider

|

Vertical Divider

|

Vertical Divider

|